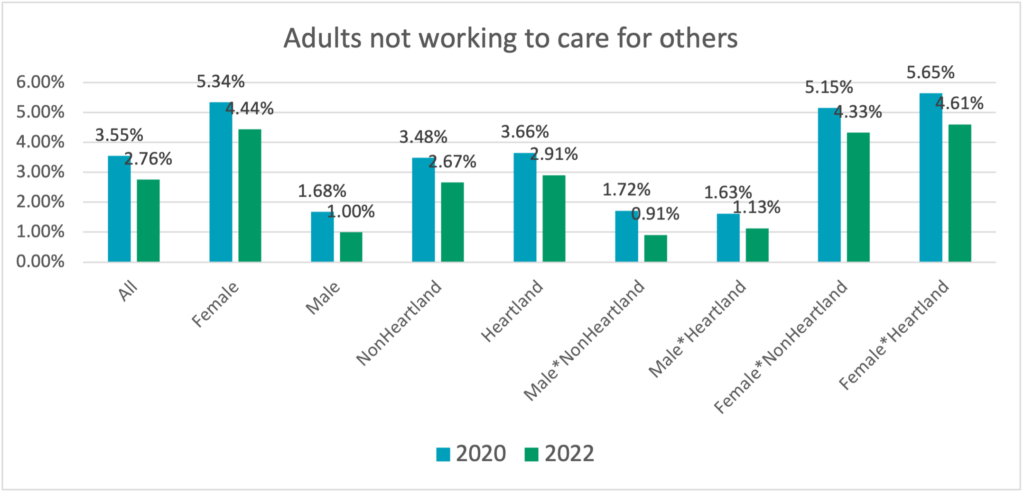

During the pandemic as schools shifted to virtual classes and daycares were closed, much attention was focused on adults unable to work since they needed to care for others. In October 2020, Heartland Forward published a blog post sharing that 5.34% of women were unable to work due to care arrangements, and women located in the heartland were even more likely to be out of work to care for others.

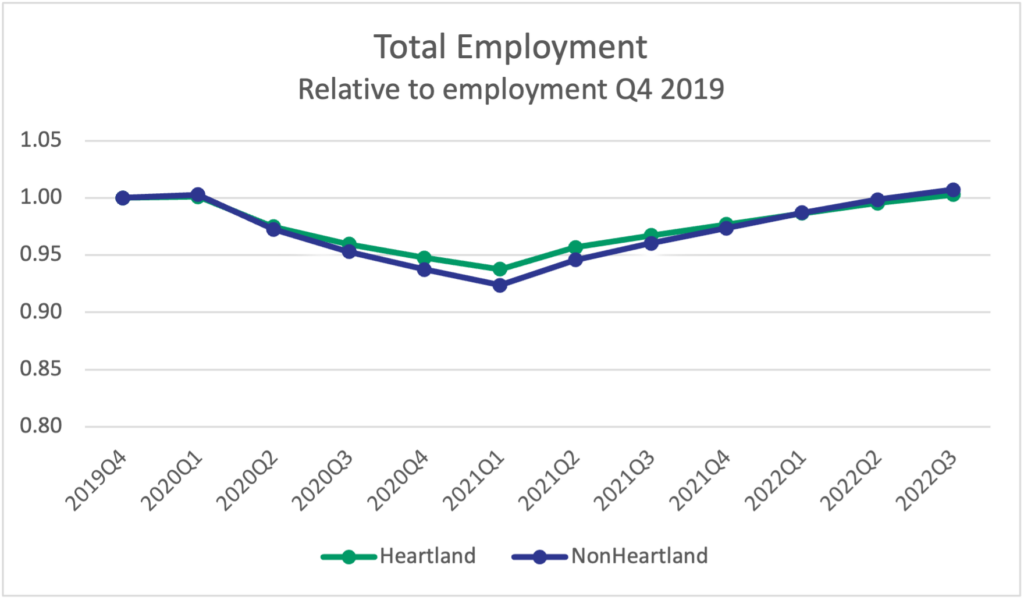

Since then, overall employment has rebounded to pre-pandemic (Q4 2019) levels, so you might assume trends have returned to normal – even those caring for others might improve. Unfortunately, the number of adults who cannot work due to care obligations has improved by less than 1%. A deep dive into the data tells an even more profound story. While fewer people are missing work to care for kids, more are missing work to care for seniors. Surprisingly, there is an uptick in men living in the heartland who are providing care for seniors.

For the updated analysis we use data collected in the Household Pulse Surveys from March 2 – August 8, 2022[i] and combine it with the data collected from the early waves of the survey in 2020. The combined dataset includes responses from over 1.2 million adults representing all 50 states. Once again, caring for others when normal care arrangements are not available keeps people out of the labor force nationwide, and it is women more often than men who miss work to be caregivers. But the percent of adults missing work to care for others is down since 2020 for men and women in all parts of the US.

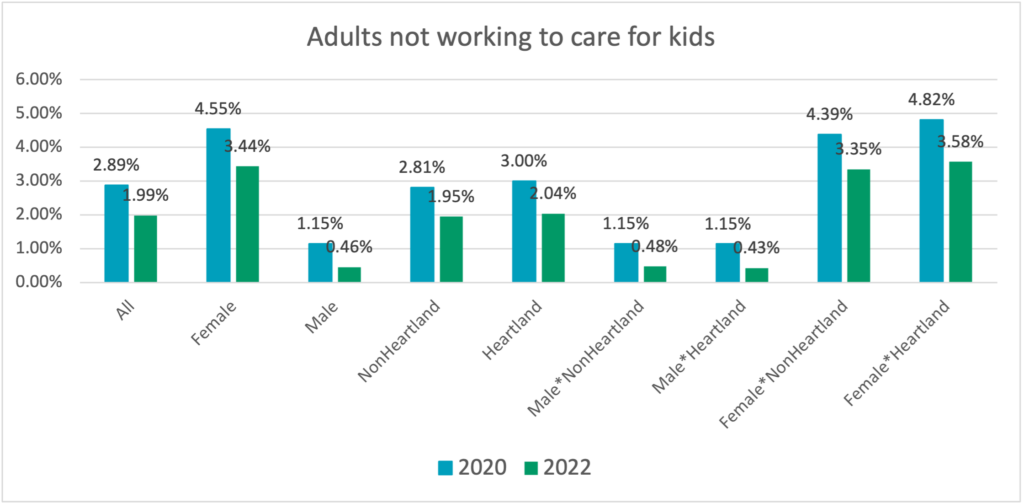

The graph above shows the decrease in not working to care for others with kids and seniors considered simultaneously. If you look at just those who miss work to care for kids the patterns are similar to the overall changes as kids are the most frequent care obligation for working age households.

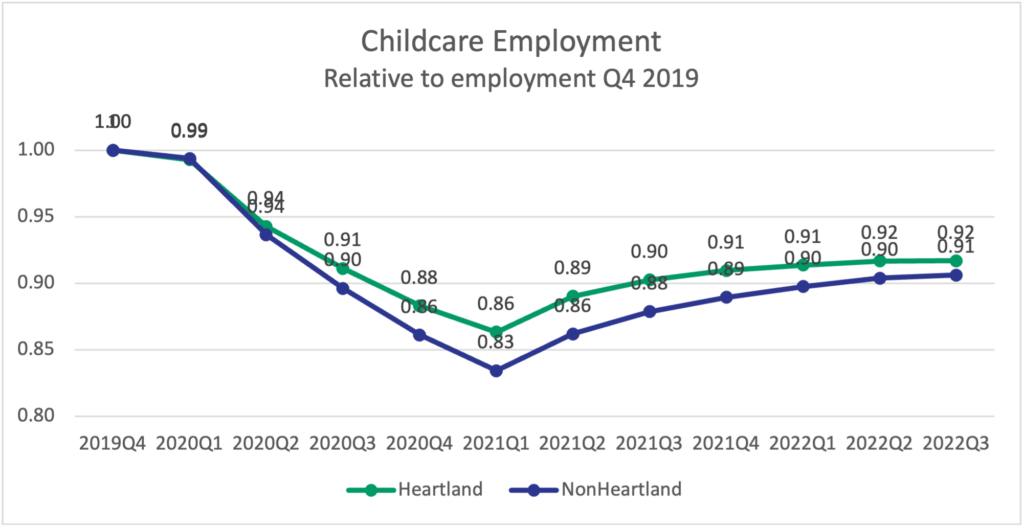

Most schools and daycare centers have reopened since 2020, but employment in childcare occupations is still about 9% lower than pre-pandemic levels,[ii] creating obstacles for parents who want to work.[iii]

Employment numbers of childcare workers explains why we still hear of parents who cannot find affordable care even though adults missing work to care for kids is down relative to 2020 as schools have reopened. This childcare employment decline occurred despite a $39 billion allocation to childcare in the American Rescue Plan Act[iiii] (ARPA).

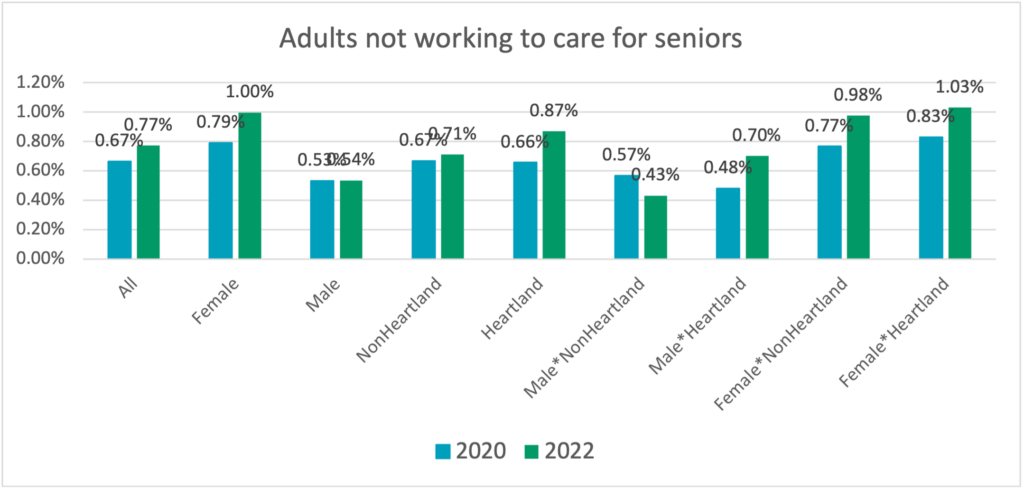

When we compare 2022 to 2020 for the rates of adults missing work to care for seniors, we see the opposite. The percentage of adults out of work to care for seniors is up. It’s up for females overall more than males. When you consider geography, we see the percent of males missing work to care for seniors is down outside the heartland but has increased for males in the heartland.

It’s important to note that these are people who would be working if not for the care obligations and not people who choose to care for others while they are out of work. The survey asks if someone has worked for income in the past week, and if not, they indicate the primary reason from a list. The respondent did not indicate that they did not wish to work, were retired, or had been laid off, but that caring for someone else was the primary reason they were currently not working.

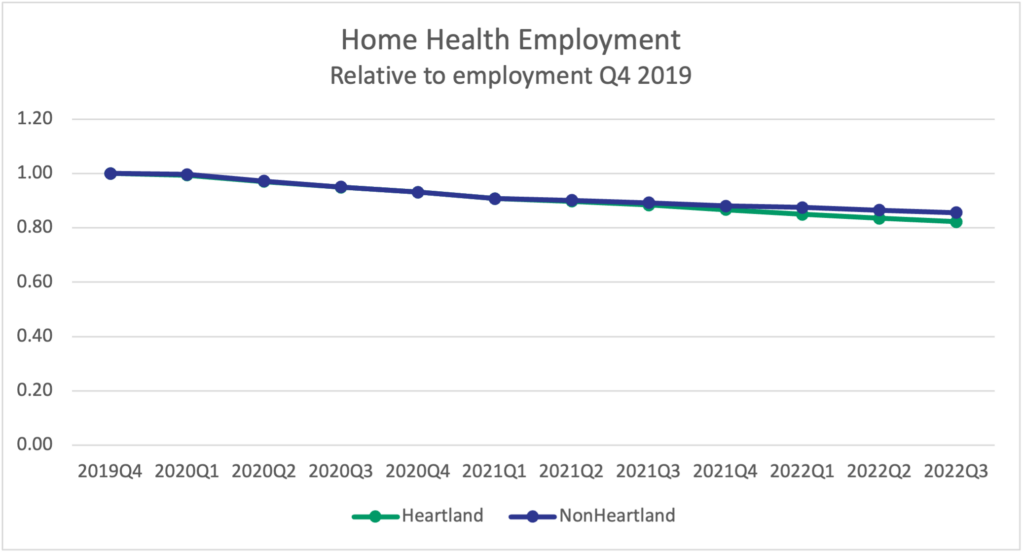

A quick look at the employment numbers of home health workers also matches much of what we see for adults missing work to care for seniors. Employment has fallen steadily since the fourth quarter of 2019 and the decline has been consistent across heartland and non-heartland states.

It’s possible people now prefer to provide care for seniors themselves rather than have home health aides come in and potentially expose a frail family member to outside risks. Or it could be that home health services are struggling to meet the demand as competition for labor and changing reimbursement policies make their financial future less viable. Whether it’s driven by supply or demand side changes, we see more adults unable to work when forced to choose between working and caring for seniors.

Of course, the home health employment data do not describe why men outside of the heartland are less likely to miss work caring for seniors while men in heartland states are more likely relative to 2020. The overall rate of adults not working to care for seniors is higher in the heartland states, so it may be impossible for females to cover all the caregiver duties without more help from men. Or that there is a higher rate of seniors who need care in the heartland. Or that the returns to employment are lower for men in the heartland, making care giving less costly.

Providing child and elder care solutions for working families is important if we want to increase labor force participation and help fill the missing worker gap. The data from 2022 show 2.76% of adults nationwide are not working due to care obligations. The complex nature of the issues requires a multi-faceted approach that will take time to build. In the meantime, employers who offer benefit and schedule flexibility so fewer employees must choose between working and caregiving are likely to fill open positions more easily and cultivate an appreciative and loyal workforce.

ENDNOTES

[ii] https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/13/us/child-care-worker-shortage.html

[iii] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/11/15/work-absences-childcare/; https://qz.com/the-us-still-has-a-pandemic-level-child-care-problem-1849954323; https://www.newstalk.com/news/majority-of-parents-miss-work-to-care-for-sick-children-1256602; https://www.axios.com/2023/02/10/labor-shortage-childcare-workers-cost-babysitter-nanny

[iiii] https://www.acf.hhs.gov/media/press/2021/child-care-funding-released-american-rescue-plan